「オバマ政権は冷戦時代の思考から脱却しろ」と

|

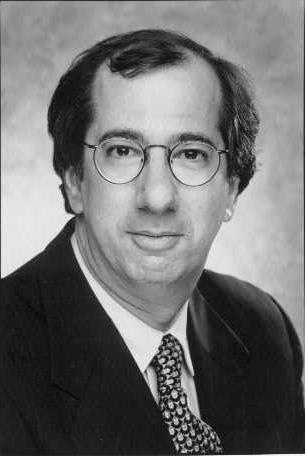

2009年10月、クリスチャン・サイエンス・モニター東京特派員を務めたダニエル・スナイダー氏とジャーナリストのリチャード・カッツ氏が、「新アジア主義」と題して鳩山外交に対するオバマ政権の対応について提言した。 ここでスナイダー氏らは、「このようなドラマティックな外交政策の変化、つまり新アジア主義を携えて、民主党は日本を導こうとしている。同党は、東アジアにおいてリーダーの役割を果たす用意があり、その意思があり、その能力がある。日本がより広範な地域的枠組みを通じて強力な中国との歴史的な対立関係をうまく処理していくことは、日米両国の利益である。ワシントンにとっては、今までより従順でない民主党日本というパートナーに慣れるには時間が要るだろうし、民主党が統治の現実を学ぶのにも時間が要るだろう。しかし、ワシントンも民主党も、冷戦時代の思考にしがみつくのでなく、これを今日的な新しい現実に合わせて日米同盟を再構築する好機とすべきである」(高野孟訳/http://www.the-journal.jp/contents/newsspiral/2009/10/post_394.htmlより)と主張した。 以下は『フォーリン・ポリシー』に掲載された全文である。 |

The New Asianism

BY DANIEL SNEIDER, RICHARD KATZ, OCTOBER 13, 2009

Since the Democratic Party of Japan won in the country’s August national election, Japan watchers have worried the new government might try to upset the status quo and ease away from the United States. The DPJ is implementing a new paradigm — but not the one people think.

Even before the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) took power, the defeated Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its American allies started running a media campaign in both countries describing the new administration as “anti-capitalist” and “anti-American.”

Critics cited an essay by new Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama in which he criticized “U.S.-led market fundamentalism” and spoke of a world in which the United States struggles to retain its dominance as China strives to become a global power. Mourning the loss of a half-century of LDP rule, these doomsayers accused Hatoyama of wanting to dump free market economics, shift Japan’s international economic center of gravity from the West to Asia, and adopt a security stance “equidistant” between the United States and China.

This characterization is as accurate as labeling U.S. President Barack Obama a socialist. Hatoyama is hardly unique in blaming excessive deregulation for the economic crisis. Far from wanting to disengage from the United States, the DPJ has endorsed a bilateral free trade agreement — something the LDP never dared. And DPJ leaders are not naive advocates of abandoning the United States only to be left to the mercies of an ascendant China. Rather, the DPJ wants a paradigm shift in Japanese foreign policy, one which makes it a more equal partner to the United States and puts greater emphasis on Japan’s ties to the rest of Asia, particularly China and South Korea.

Let’s call it the New Asianism. This ideology was on full display this weekend at a Beijing summit for leaders from China, South Korea, and Japan. It was only the second time this group of three has met. And the meeting was far more substantive than in the past, covering everything from coordinating on North Korea and economic stimulus policy to taking initial steps toward the formation of an “East Asian Community,” modeled on the European Union.

The New Asianism pushes back against, but does not entirely reject, Japan’s prioritization of its alliance with the United States. Too often, the DPJ thinks, conservative governments lined up with Washington even when they believed its policies to be misguided. For instance, former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi dispatched troops to Iraq and refueled U.S. vessels in the Indian Ocean not out of support for U.S. policy, but to ensure the United States’ favor in case tensions arose with China or North Korea.

When it comes to a rising China, the DPJ rejects containment, advocated by neoconservatives in both Tokyo and Washington, as doomed to failure. Given the United States and China’s increasing economic interdependence and overlapping strategic interests, Washington will never form an anti-Beijing front, DPJ thinkers say. Nor can Tokyo rely solely on the U.S.-Japan security alliance to counter any Chinese bid for regional hegemony. On the contrary, the greater fear in Tokyo is that the United States will abandon Japan by forming a U.S.-China “Group of Two,” relegating Japan to second-level status in the region. In the DPJ’s view, Japan needs to draw China into broader regional engagement instead.

This paradigm shift — articulated by Hatoyama and other DPJ heavyweights, in the Japanese press and in interviews with the authors — has three broad elements.

First, as Hatoyama told Obama in September, the U.S.-Japan alliance will remain “the cornerstone” of Japanese foreign policy. It makes no sense for Tokyo to distance itself from Washington on security or economic grounds, even if a few Japanese wonks entertain such fantasies.

Realistically, Japan and the United States will need each other to counterbalance China, encouraging it to become a responsible world power in terms of trade, the environment, and other issues. Plus, it would be impossible for Japan to cope with a nuclear North Korea without a strong alliance with United States (and China). Some difficult bilateral security issues — such as the long-standing problem of U.S. military bases on Okinawa — remain. But DPJ leaders, stronger negotiators than their LDP counterparts, are seeking compromise on this issue and others ahead of Obama’s November visit to Japan.

This realism has deep roots. For instance, Hatoyama and other DPJ party leaders supported expanding Japan’s security role within the framework of a strong U.S. alliance from the days when they were still members of the LDP. In 1992, they spearheaded Japanese participation in overseas peacekeeping operations. Earlier this decade, they backed a dispatch of Japanese naval forces to the Indian Ocean in response to the September 11 attacks. And this week, an envoy from Tokyo visited Afghanistan and Pakistan, a clear sign that Tokyo will continue to provide assistance on that front (though via economic, not military, aid).

On the economic front, even if Japan under the DPJ did join an Asian bloc, it would not mean the end or even the weakening of economic ties with the United States. Put bluntly: Asian growth is intimately tied to prosperity in the United States. Although Japan today exports more goods to China than to the United States, China’s prosperity is, in turn, tied to its own U.S.-bound exports. Anyone who doubts the reality of this dependence need only look at how hard the U.S. recession and its Chinese aftershock hit Japan.

The second element in the DPJ foreign-policy paradigm shift is a desire for Japan to play a regional leadership role in East Asia — a desire which might result in an East Asian Community modeled on the early stages of the European Union.

At the United Nations in New York last month, Hatoyama shared his somewhat romantic desire that in the long term such a community might establish an Asian version of the euro. He made it clear that this will be a long process, “starting with fields in which we can cooperate — free trade agreements, finance, currency, energy, environment, disaster relief, and more” and only later moving on to the common-currency question. He also stressed that the creation of an Asian currency would not hurt the dollar or strong economic ties with the United States. Rather, Hatoyama called for “sharing each others’ economic dynamism based on the principle of open regionalism” — the final term a code for informal U.S. inclusion.

Japanese government figures tentatively say that the East Asian Community might consist of the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (which includes Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei, Vietnam, Burma, Laos, and Cambodia), plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and India. This grouping first gathered in 2005; at Japan’s insistence, and with U.S. encouragement, the last three participants were added to undermine China’s bid to lead it.

DPJ advisors advocate the pursuit of the East Asian Community as only one regional priority. Another is a regional security program that might grow out of the six-party talks on North Korea. They also embrace the idea of a Japan-U.S.-China strategic dialogue, based on some DPJ thinkers’ belief that only Washington and Tokyo together can temper Beijing. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Jeffrey Bader, the National Security Council’s senior director for Asian affairs, also support triangular talks; Bader promoted this dialogue at the Brookings Institution.

Obama administration officials such as Kurt Campbell, assistant secretary of state for East Asia and the Pacific, have publicly embraced the goal of Japan improving its ties to China and the rest of Asia. Nonetheless, Obama officials are privately unsure of what Hatoyama really means when he talks about an East Asian Community. They harbor fears that this could drift into an exclusionary version of regional integration. Those fears are not entirely unfounded. But it is important to understand that this is still an amorphous concept in Tokyo.

Thus, the Obama administration needs to engage Tokyo on this issue. To do that, it needs to figure out its own policy on East Asian regionalism — before the November Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit, which Obama plans to attend. Then, Washington will know what questions to ask about the Asian version of the European Union. (For instance: How will it interact with overlapping structures, such as APEC?) And the United States can support Japan’s taking a leadership role, which it has long advocated.

The third element in the DPJ’s foreign-policy paradigm shift is a new focus on the history question: the resolution of lingering tensions between Japan and its Asian neighbors over Japanese aggression in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1995, Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama, a Socialist in coalition with the LDP, apologized for Japan’s role as a wartime aggressor in Asia. The LDP paid lip service to the apology, but its leaders frequently repudiated it, rankling Seoul and Beijing.

But Hatoyama has gone out of his way to raise this issue in all his meetings with Asian leaders, personally reaffirming his government’s adherence to the 1995 apology. The DPJ has said it wishes to remove war criminals from the Yasukuni shrine to Japan’s war dead. And the foreign minister has proposed that Japan, South Korea, and China jointly prepare a history textbook, as European countries did to confront World War II and the Holocaust. This confronting of an uncomfortable legacy is intended not only to improve ties with China and South Korea, but also to foreclose the possibility of future backsliding.

With these dramatic foreign-policy changes — this New Asianism — the DPJ is leading a Japan ready, willing, and able to play a leadership role in East Asia. It is in the interests of both the United States and Japan for Tokyo to manage its historic rivalry with a powerful China through a broader regional structure. It will take time for Washington to get used to a less pliant partner and for the DPJ to learn the realities of governance. But rather than clinging to a Cold War mindset, Washington and the DPJ should seize this as an opportunity to reframe the alliance for today’s new realities.

* http://www.foreignpolicy.comより